UnDivided

UnDivided UnBound

UnBound The Shadow Club Rising

The Shadow Club Rising Scorpion Shards

Scorpion Shards UnWholly

UnWholly Tesla's Attic

Tesla's Attic UnSouled

UnSouled Unwind

Unwind Violent Ends

Violent Ends The Eyes of Kid Midas

The Eyes of Kid Midas Chasing Forgiveness

Chasing Forgiveness Everfound

Everfound Downsiders

Downsiders The Schwa Was Here

The Schwa Was Here UnStrung

UnStrung Edison's Alley

Edison's Alley Duckling Ugly

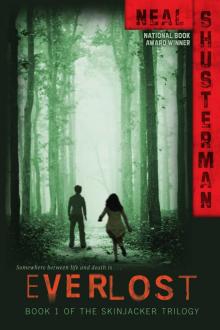

Duckling Ugly Everlost

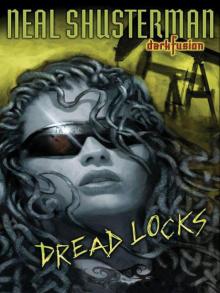

Everlost Dread Locks

Dread Locks Antsy Floats

Antsy Floats Full Tilt

Full Tilt Thunderhead

Thunderhead Scythe

Scythe Everwild

Everwild Challenger Deep

Challenger Deep Shattered Sky

Shattered Sky Red Rider's Hood

Red Rider's Hood Hawking's Hallway

Hawking's Hallway Antsy Does Time

Antsy Does Time Darkness Creeping: Twenty Twisted Tales

Darkness Creeping: Twenty Twisted Tales Bruiser

Bruiser Thief of Souls

Thief of Souls The Toll

The Toll Darkness Creeping

Darkness Creeping Resurrection Bay

Resurrection Bay Thunderhead (Arc of a Scythe Book 2)

Thunderhead (Arc of a Scythe Book 2) Everwild (The Skinjacker Trilogy)

Everwild (The Skinjacker Trilogy) Everfound s-3

Everfound s-3 Edison’s Alley

Edison’s Alley Everwild s-2

Everwild s-2 Dry

Dry Skinjacker 02 Everwild

Skinjacker 02 Everwild Everlost s-1

Everlost s-1